Once you’ve read through the notes, you can check out the Chapter 4 exercise solutions, although I strongly suggest trying them on your own first.

- Compute + memory architecture of GPUs → performance optmization

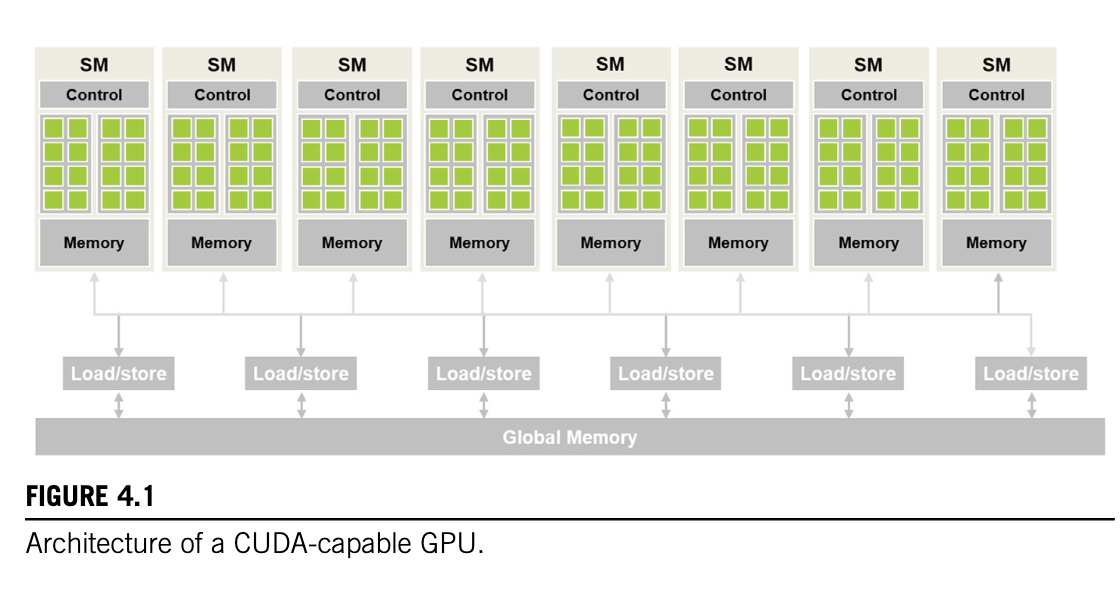

Architecture of a modern GPU

-

Streaming Multiprocess (SM): highly threaded, each has multiple streaming processors/CUDA cores (or just cores)

-

Memory: On chip memory, fast access

-

Global Memory: Larger pool of memory, slow access (DRAM/HBM)

Block scheduling

- Each block gets assigned an SM, each SM usually has multiple blocks

- Threads in each block reside on the same SM, hence have access to shared resources and can interact with each other

- Threads across blocks can interact with careful consideration - barrier synchronization

- Considerations for # blocks in SM etc later

- Most grids contain more blocks than GPU can execute simultaneously, hence runtime system (?) tracks which blocks have to be executed, and assigns new blocks to SM when previous ones finish

Barrier Synchronization

-

Each thread in the block can be synced at a particular instance in computation i.e. if a thread finishes computation sooner it can be made to wait until other threads in the block catch up

-

__syncthreads()in CUDA API achieves this -

All threads must be synced, no conditional syncing etc as its behaviour is undefined.

- Can lead to deadlock, threads waiting for other threads to reach the sync barrier

-

This enables threads to coordinate activities.

-

All threads in a block are executed roughly at the same time, and the runtime ensures that they get scheduled together in order to avoid wasting resources

-

Blocks can be scheduled and executed in any order in the grid. Thus the GPU has a lot of freedom in how it allocates, schedules and executes a computation across the grid

Transparent Scalability

- Ability to execute same application code at many different speeds

- Enables same code to be run on different devices e.g. computer, mobile, datacenter

Warps

-

Blocks can be executed in any order. Once a block is assigned on SM, it gets divided into smaller units called warps. Warps are units of thread scheduling (groups of threads that are executed together) in the SM

-

In CUDA, warps are usually 32 threads (not necessarily, depends on hardware). Blocks are partitioned into warps based on indices:

- In a 1D block, they are arranged linearly by index with consecutive threads forming a warp e.g. threads 0-31 in warp 1, threads 32-63 in warp 2

- In a 2D or 3D block, the warps consist of row-major linearized consecutive threads e.g. in a 4x4 block, threads(0, 0) to threads (3,3) form one warp. If there are not enough threads to fill up a warp, it is padded with inactive threads (e.g.) 16 threads in this case

-

Since warps run the same program in step on different indexes in the date, this type of computation is called “Single Instruction Multiple Data”. In the case of CUDA and warps, the SIMD threads are operating in lockstep, hence it is called Single Instruction Multiple Thread

-

Warps are designed to exploit SIMD hardware, each SM is divided into processing blocks e.g. A100 SM 64 cores = 4 x 16 processing blocks. Threads in a warp are assigned to the same processing block. At any instant in time, a single instruction is fetched and run on all threads in the warp at the same time by the processing block

-

Warps use the same control hardware to schedule and execute threads at the same time, thus they are advantageous because it allows the GPU to save on control resources and allocated more resources to arithmetic operations

Control Divergence

-

When control flow diverges (e.g. if-else statements, certain threads follow one control flow others follow a different control flow)

-

Warps process threads in one control flow, while others are paused, and then vice versa. So the SIMD architecture has to take multiple passes through the warp. Multipass allows SIMD hardware to implement full CUDA semantics.

-

Before Volta architecture, each pass through different execution flows was carried out sequentially. Since Volta architecture, independent thread scheduling allows concurrent processing of divergent control flows by interleaving threads which are executed.

-

Similarly, divergence can occur due to for loops, or in cases where the threadIdx determines which thread has to be processed versus not, e.g. boundary conditions in tiled matrix multiplication

-

Important to account for control divergence to reduce latency when designing warp algorithms. As vector size increases, the effect of threads being inactive due to control divergence decreases.

Warp Scheduling and Latency Tolerance

-

Many more threads/ warps assigned to an SM than it can run at one time

-

If one warp is waiting for a longer time due to waiting for a command execution to finish e.g. global memory read, the SM can not execute that warp and run a different warp while the previous waits

-

If multiple warps are ready to be executed, a priority mechanism is in place to select which warp to execute

-

Improves ‘latency tolerance’ i.e. warps that are waiting for pipelined floating-point arithmetic, or branch instructions, or waiting for a memory read operation do not slow down the rest of the execution since they get de-prioritized

-

Warps which are waiting for execution do not introduce any latency to be selected “zero overhead scheduling”

- Threads are program (code) + state of execution of program (instruction being executed, value of variables and data structures)

- von Neumann computer - code of program in memory, PC keeps track of address of instruction being executed, register and memory hold variables+data structures

- Context-switching: threads sharing a processor. By storing and restoring PC and variables+data structures, threads can be suspended and resumed. But the saving and restoring incurs overhead in terms of execution time

- GPUs hold execution state for warp in hardware registers, so need to store and restore when switching warps. This allows zero overhead scheduling in terms of compute cycles

-

e.g. Ampere A100 GPU, SM has 64 cores but can 2048 threads assigned to it (32x) - important for latency tolerance to oversubscribe

Resource partitioning and occupancy

Execution resources in SM:

- Registers

- Shared memory

- Thread block slots

- Thread slots

Resources are dynamically partitioned to support execution. e.g. A100 can support:

- Max 32 blocks per SM

- Max 64 warps (2048 threads) per SM

- Max 1024 threads per block

If a grid is launched with block size of 1024 threads (max allowed), then 2048 thread slots are partitioned into 2 blocks. If grid is launched with block size of 512, 256, 128, 64, the thread slots are partitioned into 4, 8, 16, 32 blocks respectively.

Fixed partitioning leads to wasted thread slots → dynamic partitioning can accomodate both scenarios (more blocks, few threads/block OR few blocks, more threads/block)

Under-utilization of resources:

- Block slots unavailable Each block has 32 threads. 2048 thread slots assigned to 64 blocks. However, only 32 block slots available. Thus occupancy will be 1024/2048 threads = 50%. To fully utilize thread slots one needs 64 threads/block

- Max threads per block indivisible by block size Case: max threads/block not divisible by block size. Block size = 768. Only two thread blocks can be accommodated (1536 threads), 1536/2048 = 75% occupancy

- Registers unavailable A100 allows max 65,536 registers per SM. To run at full occupancy, enough registers for 2048 threads i.e. 32 registers per thread. If a kernel uses 64 registers per thread, max 1024 threads can be supported 50% occupancy.

Performance cliff Slight increase in resource usage can lead to significant reduction in parallelism

- Kernel uses 31 registers per thread, and 512 threads per block. In this case SM has 2048/512 = 4 blocks running simultaneously. Registers used = 31*2048 = 63,488 < 65,536. Now suppose two variables assigned in the kernel, registers used goes up to 67,584 > 65,536. CUDA deals with assigning only 3 blocks to each SM, threads per SM goes from 2048 to 1536 (100% to 75% occupancy)

Querying device properties

Compute capability specifies amount of resources available. Higher → more resources

Ampere A100 = CC 8.0

CUDA C has built in mechanism to query properties of devices

int devCount;

cudaGetDeviceCount(&devCount);→ gets number of CUDA devices

cudaDeviceProp devProp;

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < devCount; i++){

cudaGetDeviceProperties(&devProp, i);

}→ Gets device properties given device count

Relevant properties:

devProp.maxThreadsPerBlock:devProp.multiProcessorCount: Number of SMsdevProp.clockRatedevProp.maxThreadsDim[0], devProp.maxThreadsDim[1], devProp.maxThreadsDim[2]devProp.maxGridSize[0], devProp.maxGridSize[1], devProp.maxGridSize[2]devProp.regsPerBlockdevProp.warpSize